“You can’t get to the truth through a lie.” – William Patrick Patterson

What happened to the witches? This is the essential question if you look into the legacy of Carlos Castaneda and the books he wrote about his apprenticeship with a sorcerer. In the following essay, I examine this legacy based on my pre-existing knowledge of American popular culture of the late 20th century. This knowledge includes what I recall from Castaneda’s novels and also my reading of several books that have been written about the role of the CIA in shaping, nurturing, and even creating the counterculture movement that began in the 1960s. Listed below are four classics that have established a significant degree of certainty about what was once ignored as a conspiracy theory about government influence on culture:

· McGowan, David. Weird Scenes Inside the Canyon: Laurel Canyon, Covert Ops & the Dark Heart of the Hippie Dream (Headpress, 2014).

· O’Neil, Tom and Piepenbring, Dan. Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties (Back Bay Books, 2020)

· Potash, John L. Potash, Drugs as Weapons Against Us: The CIA’s Murderous Targeting of SDS, Panthers, Hendrix, Lennon, Cobain, Tupac, and Other Activists (Trine Day, 2015).

· Saunders, Frances Stonor. The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (The New Press, 1999, 2013).

The careers of many music celebrities have been investigated by these authors for the unwitting role they played in steering the youthful rebellion of the 1960s toward apolitical partying, drug use and exploration of the inner world of the psyche. Others, like John Lennon, are given their due for authentically engaging with politics and paying the price for it. In Tom O’Neil’s book, Charles Manson was alleged to have been a project of MK-ULTRA psychiatrists and covert agents who kept him out of prison to keep him active in the California hippie scene, with the end result that everyone is familiar with.

One influential artist of the era who escaped such scrutiny was Carlos Castaneda, author of a series of best-selling books that described a fictional Yaqui Indian sorcerer’s lessons about knowledge gained through judicious use of hallucinogenic drugs. The contemporary acceptance of using hallucinogens in psychotherapy can be traced to their portrayal in Castaneda’s books, though it goes back further to other sources such as the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous who in the 1930s attributed his sobriety, partially, to an experience with belladonna (a species related to one of the plants used by Don Juan).

The first book in the series was The Teachings of Don Juan, published in 1968, and the others came in quick succession. Richard Jennings, on his website dedicated to investigating Castaneda and his legacy, describes him thus:

[Castaneda] was a brilliant storyteller whose best-selling tales, drawing from other great literature and spiritual traditions, communicated useful principles in a way that was vivid and compelling for many. He also lied as casually and often in those books and his daily life as any other con man with narcissistic personality disorder. And he used his fame and storytelling talent to create a cult around him. The members of that cult were made to cut ties with family and longtime friends, and to devote themselves entirely to following Castaneda and his whims.[1]

The information provided on this site is based on the experiences of Richard Jennings and Amy Wallace, both students of Castaneda and members of his cult in the years before his death. It is also based on extensive research into court and other records, and numerous interviews with other cult members, and former cult members, which is thoroughly documented here … This site is the only comprehensive source of this information.

Carlos Castaneda’s name, at birth in Peru in 1925, was Carlos Arana, though he made contradictory claims about this name and this date and place of birth. He immigrated to the United States in 1951 at the age of 26. In the early 1960s, under the name Castaneda (his mother’s maiden name—father issues?), he enrolled as a PhD student in anthropology at UCLA after having completed his qualifying degrees at community college and UCLA. His story before that time is obscured by several contradictory tales he told about his early life in South America. He claimed to have been raised in an elite Brazilian family, but Geoffrey Gray, in his lengthy 2024 article about Castaneda, discovered:

His father was not a dreamy academic but a struggling goldsmith and watch repairman. The family was so poor that Carlos was sent away as a child—not to an elite boarding school in Buenos Aires but to his extended family’s chicken farm in rural Brazil. He grew up dressing in hand-me-downs and cleaning out coops, not wearing crisp uniforms and reciting Latin… After moving to Lima, he attended a fine arts school for a time, yet according to later accounts, he spent his days at the racetrack, earning a meager living wagering on horses. During this period, his girlfriend became pregnant, and instead of sticking around to support her and his daughter, he fled to the United States. He never looked back. After questions were raised about the authenticity of The Teachings, a Time reporter tracked down Jose Bracamonte, one of Castaneda’s friends from his gambling days at the Lima racetrack. “He was witty, imaginative,” Bracamonte recalled. “A big liar and a real friend.”[2]

One might wonder how, being from such humble origins, he could have qualified as an immigrant, learned English well enough to write ready-to-publish ethnographic studies, or had the means to support himself in the United States. Why did the immigration authorities allow entry to a single man with no apparent skills or means of support—a deadbeat dad no less—and no sponsoring employer or relative? It is also not clear why the obvious fiction he wrote was accepted by UCLA to pass as a doctoral dissertation in anthropology and not referred to the creative writing department. The publisher of his books still categorizes them as non-fiction, long after it was widely accepted that they were fiction.

According to the philosophy Castaneda taught, biographical facts should not matter to anyone in pursuit of the truth. The truth is that truth is an illusion. Identity is an illusion, and, like all cult leaders, he told his followers to erase their past selves and cut ties with all people from their pasts.

Castaneda’s lies about his background, reputation for lying, and narcissistic abuses as a cult leader are enough to make one wonder if there was a guiding hand that brought him from obscurity in South America into the counter-cultural wave that swept the US in the 1960s. He is just the sort of artful dodger intelligence agencies would want to recruit. If one’s real identity didn’t matter, there were agencies within the US government that had exactly the same philosophy. They were experts in crafting false identities for operatives who could be assigned to long-term infiltration projects. And South America at the time was full of anti-communist true believers who would jump at the chance to take up the adventurous life of an operative under deep cover. Spycraft goes hand in hand with creative writing. There is a long list of spies who wrote novels, some of which were pulp and some of which are classics: E. Howard Hunt (Hazardous Duty), Joe Weisber (The Americans) Ian Fleming (James Bond), Graham Greene (The Quiet American) and John Le Carré (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy). Drama and adventure were the main attractions. For someone in poverty like Castaneda, the calling to work as a covert operative would have had immense appeal. It would also be a great way to escape from life as a racetrack hustler and the dreary responsibilities of being a father and husband. It is also possible that Castaneda’s recruitment happened without his knowing its ultimate purpose. It might have occurred, for example, under the cover of an offer of a scholarship from a foundation indirectly financed by a US government agency.

The CIA would have been thrilled to find in South America a devoted, intelligent anti-communist with a narcissistic personality disorder, someone who could be inserted into academia and publishing to be an influencer, in some form yet to be determined, in a philosophical movement that would divert mass behavior away from political organization. Assets like Charles Manson would take the low road in this endeavor, while others like Carlos Castaneda could take the high road, targeting a different social stratum. Many such assets must have gone unnoticed, but, if my theoretical speculation here has substance, Castaneda is an example of someone who hit the ball out of the park. You can look long and hard at his writings and you will find no words of wisdom about how to end the war in Vietnam, advance civil rights, help the Black Panthers, or reduce urban poverty. There were certain racial demographics in the United States that had absolutely no interest in the teachings of Don Juan in the spring and summer of 1968 when cities were burning after the MLK and RFK assassinations.

Of course, one can go too far in seeing the powerful influence of the CIA everywhere. The agency’s work was actually quite easy because there were just so many who wanted to believe that there was something exciting beyond mundane reality and that social change could come from inner transformation. It was nice to think that the old Indian sitting on a bench at the bus stop could have been a crow a minute ago. Now he is a sorcerer with secrets to reveal, if I know how to ask. The coyotes in my backyard haven’t come to the city to eat my cat. They are messengers from the spirit world who have something to tell me, if I have ears to hear them. An amusing aspect of the stories is that don Juan says he decided to take on Castaneda as an apprentice because he could tell he was “the chosen one.” Thus, the fans of Castaneda, who were too hip to go along with the squares of mainstream society, were basically reading a Harry Potter story.

If Castaneda were a government asset, this would explain UCLA granting him undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral degrees for his works of fiction passed off as factual ethnographic studies. I speculate here that everyone knew it was bullshit—not later but at the time—but somebody got a call, and forces were in play to let it pass. Once a buzz had been created, the publisher slapped a low paperback price on it, then the CIA planted positive reviews for it through their assets in the media and academia (Castaneda made it to the cover of TIME in 1973). A cultural movement was born.

This theory is more plausible considering that Castaneda turned the success of his books into a thriving seminar and workshop business, making it blend in with other self-help phenomena and pop religions that blossomed in the New Age era. These were basically revival tent meetings for people who thought themselves too sophisticated to join fundamentalist Christian churches. These were such movements as The Human Potential Movement, Esalen, Scientology. Jim Jones’ People’s Temple was in a class by itself because it mixed religion with Marxism. Castaneda was, in fact, referred to by some as the father of this New Age movement. If the phenomenon had ended with his books, there would have been no cult and no workshops, no one to be suspicious or put off by his selling out and drifting into cult formation, and the novels would have stood on their own to have a more lasting and influential legacy. However, for skeptics, the cult followers and workshops made it seem like the project had gone from shamanism to sham very quickly.

It looks, in retrospect, much like other movements from the counterculture that turned people away from politics and inward toward drugs, spiritual journeys of self-actualization, or to adjustment therapies that would help them thrive within the existing social structure. The first book inspired thousands of fans to seek peyote from Native Indian tribes, causing them to protest the distortion and disruption of their communities. Castaneda portrayed his shaman protagonist as shocked by the reckless, unguided recreational drug use of the youth. In the first book he made it clear that “learning about ‘Mescalito’ is a most serious act,” but that couldn’t stop the tide of seekers.

Some might object that I am being too dismissive of the human potential movement and the idea that you can change the world by changing yourself. There is obvious truth in this idea. It was a goal of psychotherapy long before the New Age. In 1930, before nuclear mutually assured destruction existed, Freud wrote in Civilization and its Discontents:

Men have brought their powers of subduing the forces of nature to such a pitch that by using them they could now very easily exterminate one another to the last man. They know this—hence arises a great part of their current unrest, their dejection, their mood of apprehension. And now it may be expected that the other of the two “heavenly forces,” eternal Eros, will put forth his strength so as to maintain himself alongside of his equally immortal adversary.[3]

Or, if you prefer, as Dionne Warwick sang, “What the world needs now is love sweet love. It’s the only thing that there’s just too little of.” There are a lot of people active in politics who would do well to heal themselves before they damage the causes they are committed to. John Lennon, to cite the example mentioned above, was a figure from the 1960s who had limited effectiveness in political activism because of the effects that childhood trauma had on his emotional life as an adult. I would argue, however, that the therapeutic movements of recent decades have taken the culture too far from political engagement, and as for their potential for healing the world, they have had no effect on the wounded psyches of the sorts of people who commit themselves to Ukrainian nationalism or Zionism, to cite just two examples tearing the world apart right now. Freud, writing in the 1930s, must have been well aware of this paradox. The ones most in need of psychotherapy were the least likely to seek it.

The mysterious events that followed Castaneda’s death also suggest that government agencies may have been involved in the cleanup operation. His six favored and high-ranking female followers (brujas, or witches) disappeared soon after his death. The car belonging to one of them was found in Death Valley soon after her death, and eight years later her remains were identified in the desert soil near the place her car had been found. No one had been looking very hard. The fates of the others remain unknown. Three explanations are possible: they took their inheritance and lived abroad under assumed names. They might have committed suicide to follow their guru into the astral plane, or they were killed and thoroughly disposed of by persons unknown.

Some who say they committed suicide claim that this act was the logical and unavoidable outcome of the path they had chosen. They had cut themselves off from their past and had no alternative once their leader was gone.[4] They planned their act so carefully that they left no trace, with no hint to anyone about how, where or when they would do it. Castaneda was aware of their intention. If one accepts this theory, then it is odd that Castaneda and his cult are not remembered in the same way as Jonestown.

The counter to this theory states that the witches had been set up quite well under the terms of Castaneda’s last will, as if they had definite plans to carry on after his passing. The suicide pact theory is also weakened by the fact that so many other followers kept Castaneda’s seminar business going long after his death. There were indeed alternatives for the witches. Furthermore, such group suicides seldom go as planned. People change their minds at the last minute, and things get messy when the plan gets discarded and the diehards resort to murder of the ones who hesitated (but perhaps the ones who hesitated should be called the “diehards” in this case). It is far more plausible that the witches had arranged false identities, new passports and a ride to the airport with a fixer, but the fixer then took them on a surprise detour to long-term parking (look up the fate of Adriana in The Sopranos to get the reference). Did anyone see the irony here in a cult of Western civilization, a supposed alternative to Christianity, finishing with the persecution of witches?

The group suicide theory doesn’t explain how they could carry out a group suicide and leave no witnesses and no bodies that would be discovered by someone sometime in the future. There is only one type of group in society that can make this kind of disappearance happen, and they usually operate in the desert closer to Las Vegas. The witches, however, were just gone. No one saw them pack up and leave, and there was apparently nothing strange about their disappearance. No one who knew them felt the need to look into the matter any further. This was, after all, what their master had taught everyone to do: escape from the limitations of rational thought.

Tensegrity was the theory that was taught at workshops organized by Cleargreen Inc., the business arm of the cult. They also produced motivational videos, sold T-shirts, and recruited new witches. Cleargreen continued to operate for more than two decades after Castaneda’s death, gasping its last breath, ironically, during the years of the covid psyop. According to the reports by Richard Jennings (at sustainedaction.org), the people who took over the management and ownership of Cleargreen never explained what happened to the substantial financial assets generated by Castaneda’s work. They claimed to have no answers about or interest in what happened to the missing high-ranking witches, nor did they satisfactorily explain to skeptics why they had the rights to manage Cleargreen. The books still sell well and generate royalties for whatever entity is now the legal heir to them.

Castaneda was dying of liver cancer in 1998 when he signed his last will at his lawyer’s office, in front of witnesses who all claimed he was mentally competent. He died a few days later from liver failure. The liver problem involved metabolic encephalopathy—a condition that causes personality disorder, memory loss, and difficulty in thinking, all of which occurred, apparently, only after he signed his last will and testament.

This description of Castaneda’s life and works is a quick summary written after a short journey down the rabbit hole of reports, cited in the Notes, on the cult that existed around him. This was written with little consideration of the content of Castaneda’s books that I read and loved when I was in my twenties. No one can deny that they contain some excellent insights. I may have got some details wrong here. This is just prima facie speculation, but a superficial review of the case is enough to nominate the Castaneda story as possibly one of the many covert operations that shaped the culture of the late 20th century.

The numerous critics who are outraged by the unresolved mysteries might do well to consider the possibility that powerful unseen entities made sure that the loose ends of their operation would be swept away and buried in the same hole as the files concerning Jim Jones, Charles Manson, JFK, RFK, MLK, Malcolm X, and other such cases. This should be apparent in the fact that all the officials and lawyers in a position to investigate chose not to look very hard. Like the LAPD detectives who didn’t want to ask the obvious questions about the Robert Kennedy assassination that occurred in Los Angeles, they knew implicitly that the case reeked of a covert government operation, probably with collaborators on the police force. Asking questions would not be conducive to career advancement, to say the least.

It is plausible that Castaneda was recruited in South America, trained and given a cover, then inserted into the intellectual life of the United States. His frequent disappearances from Los Angeles to go wandering in the desert with Don Juan might have been time spent in libraries or with his handlers and ghost writers, all of whom might have found their creative writing project very amusing and challenging. I would bet also that Castaneda was a popular author among CIA staff because the teachings could be equally useful to both hippies and covert agents. Furthermore, the question of ghost writers connects to another issue no one wondered about: The dialogs with Don Juan obviously occurred in Spanish, and Castaneda made a very impressive rendering of them into American English, a language he likely did not speak at all before immigrating to the US in 1951 at the age of 26. No translator or co-author is credited with helping him craft native-like idiomatic English prose. But perhaps he was just that good. I digress.

When his writing struck bigger than anyone could have expected, it was transformed into a cultish, anesthetic psychotherapy movement. When he died and the cult leaders presented too many loose ends to deal with, the cleanup operation was activated. Once the higher level was eliminated (the people who knew too much), Cleargreen, a remnant of the organization, was allowed to die a natural death on the margins of a society that was quickly moving on. There weren’t a lot of seekers going on walkabouts after September 2001. The New Age was in old age, and Castaneda’s works declined in influence, probably largely because they were, with embarrassment for the publisher and UCLA, understood to be works of fiction, and because of the unseemly events that followed his death.

The millions of right-thinking educated seekers who were devotees of the books (not at all to be confused with those low-life Manson and Jonestown deplorables) would be slow to consider the possibility that they had been taken for a ride by a sophisticated intellectual who compiled his philosophy from whatever snippets of eastern mysticism he could find in the UCLA library.[5] They dismiss Castaneda’s critics and deny that he was a textbook example of a narcissistic liar and cult leader. His deceptions and fabrications were, they say, his creative genius’ method of teaching how to shed the ego and find the path of the warrior. Who cares if he lied about the veracity of his work, or his true identity and details of his past? He was a self-described trickster. If you’re the kind of person who thinks personal integrity and family connections and responsibilities are important, then you are just too hung up in your ego and conventional morality to appreciate the brilliance. Unlike Manson, Castaneda did not creep people out, and he could write coherent and compelling prose. And unlike Jim Jones, he wasn’t actually taking concrete steps to help the poorest segments of the US population. These are the reasons I say he might have simply been the highbrow version of other psyops that were carried out in the 1960s. Fools might come around and admit that they were duped, but educated fools take much longer.

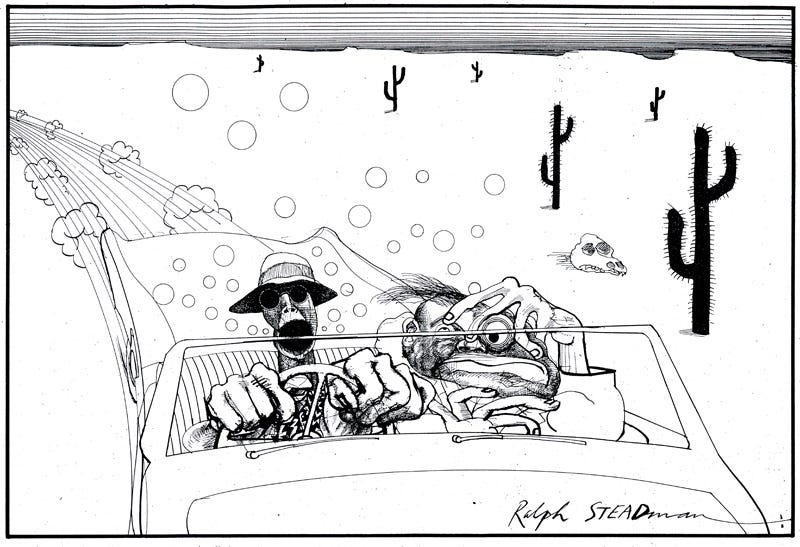

“We are all wired into a survival trip now. No more of the speed that fueled that 60’s. That was the fatal flaw in Tim Leary’s trip. He crashed around America selling “consciousness expansion” without ever giving a thought to the grim meat-hook realities that were lying in wait for all the people who took him seriously... All those pathetically eager acid freaks who thought they could buy Peace and Understanding for three bucks a hit. But their loss and failure is ours too. What Leary took down with him was the central illusion of a whole lifestyle that he helped create... a generation of permanent cripples, failed seekers, who never understood the essential old-mystic fallacy of the Acid Culture: the desperate assumption that somebody... or at least some force—is tending the light at the end of the tunnel.”

- Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream (1971)

Notes

[1] Richard Jennings, “Investigating Carlos Castaneda and his legacy/Intro,” July 2024.

[2] Geoffrey Gray, “The Case of the Missing Chacmools,” Alta, June 20, 2024.

[3] Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents (London: Hogarth Press, 1930), 144.

[4] Robert Marshall, “The Dark Legacy of Carlos Castaneda,” Salon.com, April 12, 2007.

[5] Patterson, William Patrick. William Patrick Patterson Explores the Life & Teachings of Carlos Castaneda (52-minute lecture, YouTube, 2013). Listen to this lecture for a point of view opposed to the one I have taken above. Mr. Patterson gives high praise to Castaneda in this lecture and dismisses the concerns people have had over the years about everything discussed above. (“The brilliance of his early near-archetypical renderings of non-ordinary reality clash with his accrued reputation as a manipulator, liar, and trickster, and that, no doubt, is the way he would have wanted it. He leaves us not knowing and questioning”). However, later in the lecture, he makes the statement that I quoted at the beginning of this essay: “You can’t get to the truth through a lie.” (28:56). This indeed leaves me not knowing and questioning.